Beyond Intentions: Consequences of Design

“Such reasonings and all reasonings turn upon the idea that if one exerts certain kinds of volition, one will undergo in return certain compulsory perceptions. Now this sort of consideration, namely, that certain lines of conduct will entail certain kinds of inevitable experiences is what is called a practical consideration. Hence is justified the maxim, belief in which constitutes [P]ragmatism; namely: In order to ascertain the meaning of an intellectual conception one should consider what practical consequences might conceivably result by necessity from the truth of that conception; and the sum of these consequences will constitute the entire meaning of the conception.”

The following case studies are analyzed via the theoretical framework of "beyond intentions: consequences of design."

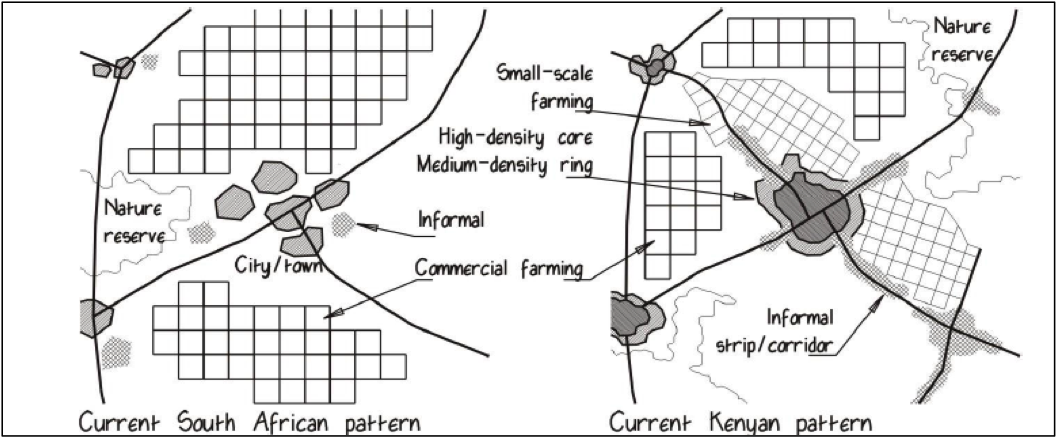

Khayelitsha township, South Africa

Through examining the consequences of design for Violence Prevention through Urban Upgrading (VPUU), a community-based slum upgrading program in Khayelitsha Township, South Africa, the understanding of transformative urban practice can move beyond intentions and into real-life consequences. In response to high rates of crime and unemployment, the government of Cape Town launched a series of programs aimed at upgrading the infrastructure of townships, including the VPUU initiative. Its main intention was to reduce incidences of crime and improve safety for the residents through a design process that would deliver urban upgrading along with broader social interventions. The VPUU team was multidisciplinary and integrated community participation into the design process via participatory and civic means.

The VPUU project has received wide recognition as a particularly successful urban renewal program by both scholars and policy makers alike. In its six years of operation, the VPUU project has achieved success in lowering the crime rates in the notoriously poor and dangerous South African township. This success is not only attributed to good design, but more significantly to the design process, which prioritized community participation and empowerment in the planning, governing and maintenance of the project. The notable success of the VPUU project in the Khayelitsha Township can be attributed to the efforts of the design team in producing desirable consequences through their practice.

**Case study analyzed by Zung Nguyen

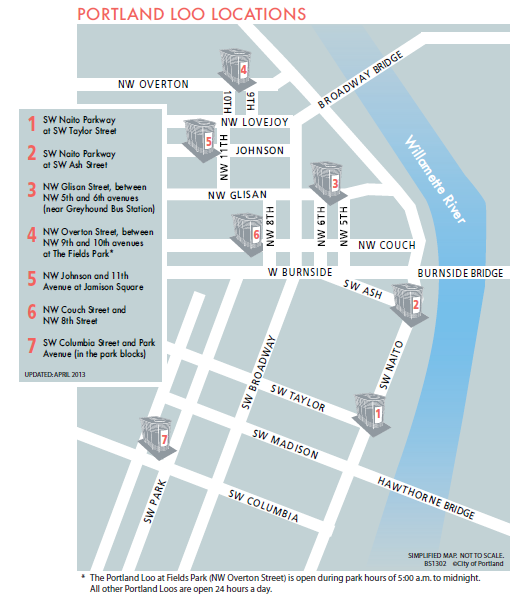

Portland Loo, Portland

Portland Loos are simple, sturdy, attractive flush toilet kiosks located on sidewalks in public areas. The loos are maintained by the City of Portland in Oregon and free to the public and accessible around the clock every day of the year. Portland Loos give the community clean, safe and environmentally-friendly restroom facilities. Above all, the Portland Loo Case Study investigates the question: what are the consequences of prioritizing the design of sanitation infrastructure in a city?

The Portland Loo demonstrates how prioritizing an overlooked element within cities, like public toilets, can lead to large-scale urban transformation. The Portland Loo was most transformational in promoting a new narrative about public sanitation. Through the celebration of sanitation, The Portland Loo is "humanized" and becomes a part of the community and a symbolic representation of the local government's investment in the sanitation rights of its citizens. This object of sanitation gains a respect from its users and transforms the communities relationship to public toilets and sanitation in general.

**Case study analyzed by Clarissa Cummings, Rebecca Rand, and Marisa Semensohn

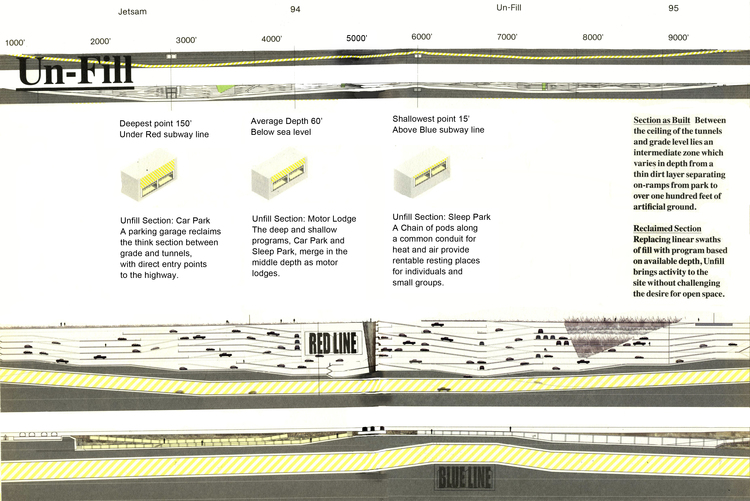

Central Artery / Tunnel Project, Boston

The Central Artery/Tunnel Project (Big Dig) is an extremely large, time-consuming, and complex project in the heart of a bustling city. Both the project’s supporters and detractors point to the often-unprecedented construction challenges as a sign of accomplishment on the one hand, and as a partial reason for its enormous delays and cost overruns. For example, the construction of the Interstate 90 extension involved some of the most complicated and challenging engineering, including tunnel jacking, the construction of a casting basin for immersed tube tunneling, and cut-and-cover tunnel construction. The reconstruction of Interstate 93 through downtown Boston was also enormously complex. Before heavy construction began, utilities had to be relocated and mitigation measures put in place. Then slurry wall construction began in the mid-1990s, which required underpinning of the existing elevated Central Artery before excavation.

The results of overcoming these challenge, albeit at great cost, include a much faster flow of traffic through downtown, increased access to the airport, increased real estate development opportunities in the area, stitching of an urban fabric that was interrupted by an elevated highway, and a series of open spaces in the heart of the city and on the waterfront. There are also unexpected consequences, such as the use of excavated soil to create a new park for people to enjoy and a house built out of recycled materials from the old elevated highway. However, the most significant consequences may be symbolic.

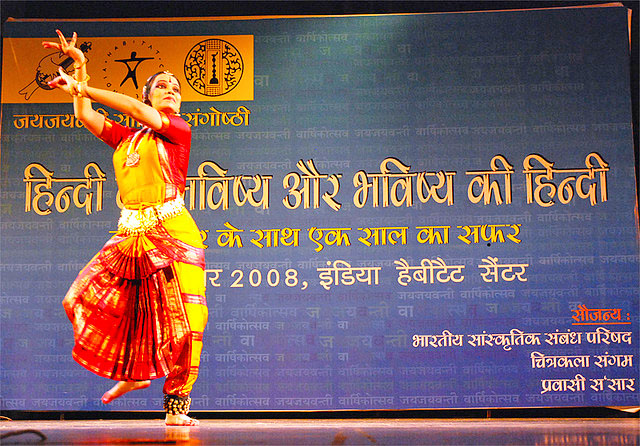

India Habitat Centre, New Delhi

Can one redesign the city by redesigning its institutions? The India Habitat Centre is ostensibly a government office building, a project initiated by the Government of India’s Housing and Urban Development Corporation (also known as HUDCO) to house its headquarters. Instead, it has become a vibrant urban center in the heart of a bustling city, New Delhi, filled with intellectual, social, and cultural activities that comingle. Similarly, the radical shift of the design was from office building to ecological campus.

The consequences of the particular design of the India Habitat Centre are that it is “a place that handles transportation and an enormous variety of public and private activities, from housing to bank to entertainment to food. A city within a city, it is a intellectual shopping center that provides [food], great theater, cutting edge art . . . and wonderful outdoor spaces that are comfortable even in summer. The India Habitat Centre has made an extraordinary contribution to the city of Delhi.” Indeed, one regularly finds dance and music performances, art and photography exhibitions and workshops, book readings, international conferences, and even groups of children visiting and drawing at the Center. The Center exudes a vision of urbanism that is exemplary.

Centre Pompidou, Paris

The Centre Pompidou took the architecture world by storm through its highly-visible steel frame structure, large-span flexible exhibit spaces, its brightly-colored services such as water and ventilation pipes on the exterior of the building, an all-glass façade that created multiple transparencies, and spaces that include a mediatheque, a state of the art film theater, a library open to the public, a restaurant with a stunning view of the city, and multiple exhibition spaces that attracts millions of visitors every year.

At the same time, this singular building generated a larger scale transformation of the urban area. As the Centre Pompidou attracted increasing numbers of Parisians and visitors, private and public investment poured into the surrounding buildings in the form of retail and residential uses. It created vibrant public spaces by facilitating magnetic attractions in the form of regular and lively street performers and a colorful, sculptural water fountain. The colorful Stravinksy Fountain attracts a mix of young and old, residents and visitors to sit on its edge, to stroll around it, and the most urban of activities—to watch and be watched.